Barriers and Blessings

Geometry class, your warm-up today is a free-write for the following prompt:

“Write one to two paragraphs about a challenge you face or something you struggle with. It can be about anything: school, parents, siblings, peer pressure, etc.”

Thank you for taking the time to write about your struggle. I am collecting your responses as a way to get to know you better and see ways that I can support you. Now, let me share my story with you. I was two years old when my parents started to recognize something was wrong. I was not talking like other children my age. One day, my dad and I were sitting on the back deck. I had my back turned to him and was in immersed in my own world of Legos and blocks. My dad decided to conduct an impromptu test:

“Lindsey,” my dad whispered. I gave no response.

“Lindsey,” he said, using a normal talking voice. I still did not acknowledge him.

“Lindsey,” he called, raising his voice, but I still did not flinch.

“Lindsey!” he shouted. I then turned my head and looked at him.

That was the day my dad figured out there was something wrong with my hearing. It took months of doctor visits and tests until they identified the root issue and fitted me with hearing aids. At that point I began to talk and progress in my development.

You know what? I love my hearing aids. Turning my ears off is amazing! Need to study in the college dorms when people next door are blaring their music? No problem—turn my hearing aids off. Need to take a moment to calm down and block out the world? Simply turn off my ears. Need to tune my mom out when she is yelling at me for not cleaning up my mess? Yes, I can turn that off too! I bet you wish you could do that!

I had you write about something you struggle with because we all have personal challenges. That is part of our human experience. We need help with the things we struggle with. I have hearing loss and I will need your help with this. I need you to speak loudly in class. If I don’t hear you, I may have others closer to me repeat what you said (so that means you all need to be paying attention, because I will put you on the spot). What questions do you have?

Over the past nine years of teaching math at three different large, public comprehensive high schools, this scenario became a staple first week of school activity for all my classes. It let my students know that I wouldn’t always hear their answers and that they needed to speak up. It also gave me a peek into each of my students’ lives. Jolene¹, who feels like the parent because she is responsible for her four younger siblings when they are not in school. Matt, who has testing anxiety and gets nauseous before a big test, no matter the subject. Alexis, who has to ride the bus one hour to school each way and doesn’t get to spend much time with her friends because she lives so far away. Then there were Tim and Jordan, students who also wore hearing aids, who came to me after class and said they appreciated me telling my story and described how theirs was similar or different. I treasured this look into my students’ worlds beyond their math class. Yet it wasn’t easy to get to a place of knowing myself enough to share my story with my students.

When I first started teaching, I felt anxious about how my hearing loss would affect my career. I worried that I wouldn’t be able to hear my students’ answers. I wondered: what if my students wouldn’t feel safe because other students would say inappropriate things and get away with it because I didn’t hear them? Then, if I really started to fret: what if I lose control of my classroom? What if I were to lose my job over something like this?

It was the first time in my life that my hearing impairment seemed like a barrier rather than a blessing. Turning off my ears was normal to me and felt like a personal benefit until I stepped into the flood of uncertainty and self-doubt that typically comes with being a first-year teacher. As the teacher I was now the adult in the room, not just responsible for myself but for every other person too. And, let’s be honest, that requires hearing. I was terrified of this responsibility and whether my ears would let me carry it out.

The year that I was in my master’s program and doing my student teaching aligned with my first year as a Knowles Teaching Fellow. One of the requirements of the Fellowship was to pick a goal to focus on for professional growth. Through the nudging and support of Knowles, as well as my university supervisor, I determined that my goal was to find strategies for dealing with my hearing limitations in the classroom. In this journey, I researched articles on nonverbal communication, experimented with strategies for informal assessments that don’t rely on verbal answers, and visited another teacher who has hearing loss and observed her classroom. It was this visit that single-handedly calmed my anxieties. Ms. Witzemann did not give me any major insights or secret strategies; it was simply seeing her in action and how her students responded that gave me a sense of relief. She had been in the classroom for years and not lost her job or cited any failures as a professional because of her hearing loss. I had met numerous people who wore hearing aids but up to that point had not seen one working in a professional capacity. Even though I only spent a few hours with her, Ms. Witzeman became a model for me of what it means to be a hearing-impaired teacher.

Teaching was the first time in my life that my hearing impairment seemed like a barrier rather than a blessing.

Shortly after my visit with Ms. Witzeman, I created the lesson plan that I described at the beginning of this article. This was my way of beginning the conversation with my students about my hearing loss in a way that felt safe for me as well as opening the door to conversations with students, both as a class and individually. After eight years in the classroom, I know that my hearing loss is not a barrier but continues to be a blessing.

It would be easy to stop here, to share the success of how I came to terms with my own hearing loss in my professional career and how I shared it with my students. To give you, reader, the happy ending. However, as is the case in real life, there is always more to the story.

I have another physical disability that I could not bring myself to talk about with my students. I am sure my students picked up on my odd behaviors: not seeing raised hands on the sides of the room, losing my spot while writing notes and taking a few awkward seconds too long to find it again, always missing random chunks of words and graphs while erasing the whiteboard. In fact, I had one student get so annoyed that she offered to be the designated board eraser for the class.

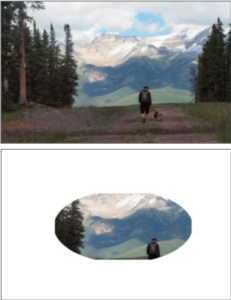

My visual world is narrowing on me and I was in denial about it. My hearing loss I see as a blessing, but I have yet to find the blessing in going blind. At 22, I was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic eye disease which starts as night blindness, continues to gradual loss of peripheral vision, then to loss of central vision, and eventually, in many cases, total blindness. Right now my visual field is a third of the typical range of vision. My central vision is clear; I just see less than normal. Imagine holding toilet paper rolls to your eyes and walking through a normal day with tunnel vision. This is my reality (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Visual fields, typical and with advanced retinitis pigmentosa.

How did this affect me in the classroom? Let’s say I drop the whiteboard marker I am using while going over a geometry proof, and it rolls across the floor. Then I spend an inordinate amount of time looking for it. A student chimes, “It’s right over there” and points to the marker. While the student is trying to be helpful, “here” and “there” are undescriptive words, giving me no visual orientation of where specifically to look. Of course I am expected to see where the student is pointing. Yet, to look at the student who spoke up, find their arm and follow in the direction where their finger is pointing is a difficult task. It might actually be faster for me to get on my hands and knees and conduct a comprehensive visual sweep than transfer those vague verbal clues onto my limited visual map. I learned to keep a good grip on my markers and if I lost a cap, I would wait until students were working independently to begin my hunt for it. I couldn’t stand wasting class time, much less putting on a public display of the ineffectiveness of my eyes.

When I first started teaching nine years ago, my diagnosis did not concern me as much, as I was not experiencing its limitations. Yet in the past few years, I have noticed the change in my vision. I talked to my friends and family about what was happening but could not talk about it at work. I was afraid that if I let my colleagues and administrators know about my changing vision, they would tell me I had to stop teaching. If I had to leave the classroom, I wanted to leave on my own terms, not because someone else told me to. And certainly not because of my eyes.

Around the same time, I started seeing a new eye doctor. After conducting a comprehensive examination, she sat down with me to discuss her findings, particularly about my limited field of vision. She expressed her concern about my ability to manage a room full of teenagers and whether they might take advantage of me. I responded by telling her that I wasn’t worried about it, that I had a positive relationship with my students, and I was managing them just fine. In the moment, I shrugged off her concern as minor. However, I left that appointment feeling frustrated and angry. She hasn’t even seen me in the classroom! How can she pass judgment on my classroom management skills? I am the professional educator, highly trained in the field, not her. Yet, I was scared because there was a jabbing needle of possibility in her concern. There may be a day when I should not be in the classroom; how would I know when that would be?

My hearing loss is stable. It is familiar and predictable, so I can adapt accordingly. I won’t hear you whisper, and it will always be that way. Either use a normal voice or write it down. Because I know what to expect of my hearing limitations, I can coach my students. My visual field, on the other hand, is always a shifting line. How can I share this with my students when I myself don’t even know what to expect? An acquaintance I met at a Foundation for Fighting Blindness event who has completely lost his vision to retinitis pigmentosa told me, “The hardest thing is not being blind, it is going blind because it is always changing and you don’t know what is going to hit you next.” That resonated with me both figuratively and literally. I was constantly running into student desks as I walked around the classroom and by the end of each week, my thighs were littered with bruises, the physical evidence from the ongoing battle between my vision and my profession.

When do we know if the best way to support our students is to share with them the challenges we ourselves are facing?

I felt I could talk about my hearing loss with my students and still retain my sense of authority. But to talk about hearing loss and vision loss together seemed to be an invitation for student rebellion. For example, I had a hard enough time with getting buy-in from my algebra class, over half of which were taking the class for the second time and dreading every moment of it. There was simply no way I felt comfortable sharing this raw part of me with them, especially as the class ring leaders and I were already on delicate footing. My pre-calculus class, on the other hand, was filled with model students who were eager to learn and emotionally aware of themselves and the people around them. I would have been willing to be transparent with them, but students talk and it would eventually get to my algebra students. I took the safe route of silence and secrecy.

As the adult figure in the classroom, being transparent with students can foster a greater sense of respect and build stronger connections. You are showing that you are human and that you have issues as well. I wonder where the line is for being transparent and being too vulnerable. I believe I have not fully taken ownership of what losing my vision means for me personally. By sharing it with 130 teenagers, I felt that I would lose myself in that transparency. But I also wanted to be real with them and I wrestled with this tension.

As teachers, we have a unique opportunity to be role models and influence young people in a way that directs the course they take. We nudge them, encourage them, coach them, invest in them and in the process, we can share so much of ourselves that our professional and personal lives get blurred. When do we know if the best way to support our students is to share with them the challenges we ourselves are facing? Or if it is better to keep that information private and be the strong shoulder on which our students can stand? I do not have a clear-cut answer for this dilemma but will continue my role as a teacher to explore ideas, ask questions, and see beyond the immediate challenge.

¹ All student names are pseudonyms.

Citation

Quinlisk, L. (2018). Barriers and blessings. Kaleidoscope: Educator Voices and Perspectives, 4(2), 14–17.