How Our “Ideals” Influence Whom We Teach: Part Two

In How Our “Ideals” Influence Whom We Teach part one, we dove into two scenarios to investigate how our educational ideals evolved and we discussed the impacts of our stories on those who were not deemed preferred. We came to three conclusions: “If we each have preferred students, how does this impact those we don’t prefer?” “It’s important to know what you really think and examine why,” and “This is all in the name of REAL equity.” We discussed the first conclusion in part one of the blog. In this second part, we share a framework that we used for more deeply investigating our assumptions in the service of more equitable classrooms.

Revisiting our scenarios:

Katey’s scenario: Public or private?

My choice to teach in public school was rooted in a perception of a social call to action, that I had to do something to address stereotyped needs in public schools. But my assumptions were not balanced by intellectual reasoning or data about either public or private schools; whether I would also benefit students in private school or what the true needs and resources are in specific urban public school settings.

Ayanna’s scenario: What do preferred students look like?

I get angry and sad when thinking about how many students of color are expected to be in a continual state of ‘underperforming’ in mathematics and how that results in fewer being enrolled in challenging mathematics classes elicits an emotional response from me. While these emotions are valid and I have collected data about the impact of tracking on minoritized student outcomes, I have not had many experiences teaching in truly heterogeneous settings and I recognize that the struggles present in de-tracked settings are in some ways foreign to me.

It’s important to know what you really think and examine why

For us, reflecting on our stories has highlighted the importance of taking the time to consider what we think about”good” students and what has encouraged or reinforced that thinking. Through this blog, we have both engaged in an investigation of our own thinking, have shared that thinking with each other, and have tried to find the missing perspective. This process of personal investigation and seeking out the missing critical perspective is a strategy discussed by Glen Singleton (2006) in the book Courageous Conversations About Race. Seeking out the missing critical perspective with respect to teachers preferences may mean talking to students who do not represent our ideal, parents of students who do not fit our ideal, and teachers who succeed with the students that we struggle to support. Seeking out these perspectives can surface for us how we have been socialized toward definitions and visions of preferred students, who exists outside of our ideals, and most importantly, how those student became unpreferred for us.

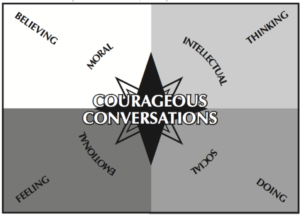

To support the examination of what undergirds your ideas, we share a framework that we have found helpful for engaging in self-reflection with respect to our own assumptions, ideas, and biases about education. The courageous conversations compass was developed to serve as a “navigational tool to guide people through conversations about race” (Singleton, 2006, p.19–20). It suggests that there are “four primary ways that people engage with racial information, events, and/or issues” (p.19): from a moral standpoint, an intellectual standpoint, an emotional standpoint, or a social standpoint. We use this compass to help us to isolate how we come to this conversation about teachers preferences about students and schools and as a way to continue digging in to what we believe and why. In this blog, we expand the intended use of this compass to consider the ways that preferred students might be conceptualized by a teacher.

The courageous conversations compass (Singleton, 2006, p. 20)

If we apply these four points to our conversation about preferred or good students, we acknowledge it’s possible that our entry to this discussion exists within one of these quadrants. That is, we may enter the conversation about preferred student by sharing our beliefs about who preferred student are, how preferred students make us feel, thinking about data on what preferred students accomplish, or envisioning what preferred students do or do not do. Reflecting on what good students look like from these different perspectives, and who fits the description, can offer any teacher keen insights into who they focus on in their career including in their daily planning, teaching, or inquiry, and why.

Our position is that no matter who your preferred student(s) or schools are, these ideals play out in your everyday decision making. For example, let’s say that a teacher gave her students a summative exam and 80% of the students passed and 20% failed the exam. While all teachers want their students to do well, how one addresses the 20% could be reflective of a teacher’s ideas about what makes a good student. If a teacher believes that preferred students seek out academic help on their own time to demonstrate an investment in their learning, then she may choose to develop a lesson plan addressing the most commonly missed questions on the exam, which would cater to the 80%, leaving the 20% to learn in another setting (e.g., tutoring, study hall, etc.). On the other hand, if the teacher believes that high test scores indicate deep conceptual understanding, then he may choose to plan a lesson addressing the 20% of students who failed the exam, which essentially requires the higher achieving students to come on their own time to understand what they missed if it is not discussed in class. While there is not a right way to address this issue, there is benefit from thinking about what we commonly do or have done in our own practice to teach our own ‘preferreds’ and why.

It’s all in the name of REAL equity

We are not writing this blog to challenge the existence of preferreds. We believe that teachers are going to exist in a world where their personal preferences guide their actions, and decisions about who to teach, where and how. Instead, we hope to maximize the reach of all teachers by encouraging teachers to expand their efforts, to include more students, by considering the needs of students who are not their current preferreds. This is a step towards real equity: towards agreeing that all students have a right to instruction that meets their needs, no matter what a given teacher’s preferences about students are.

Our call for teachers to examine why they find some students preferred and to unearth the effects of this by examining who, then, gets labeled as unpreferred, is an opportunity to reach more students. This is not about creating a false dichotomy between “bad” teachers and the rest of the teachers in the workforce, this is about all teachers (and we hope that all educators would work towards widening their preferences). We hope that, in the name of advancing the understanding among the educators in our communities, including those in the Knowles Teaching Fellows Program and the Knowles Academy, we would all become well-practiced in checking ourselves on who we are envisioning when we describe and discuss classrooms. We invite our communities to find positive lenses with which to view students and schools, to welcome back more students into our preferred pool while we work to reach them, and to be honest with ourselves as we grow as members of the education community noting who we envision more positively as a result of this work.

Perhaps there is a chance that this thinking can help us all, as members of society, examine our own assumptions about all others, not just students. Perhaps whom we do not prefer in this country or in our communities could be evaluated too, and we could honestly examine which mindset guides our thinking: emotional, social, intellectual, or moral. Trying on a different mindset might help us to see that our stereotypes are guided by one framing or another, and that our vision of whom we include and exclude from various learning, rights, privileges, assets, and status could shift towards inclusivity.

This work is challenging and personal, and yet, with tools like the courageous conversations compass, it’s possible to enter into discussion about personal assumptions and choices to both defend and push against our “preferred” thinking. In our conversations about choosing and describing preferred students and how to push past those assumptions, we’ve benefitted from telling stories to one another, identifying the mindset that’s driving our analysis, and acknowledging when we had and when we lacked data to justify our conclusions. We invite you to self-reflect and to engage others in similar ways. Ultimately, we hope that choices about who teachers teach and where, as well as who is deemed worthy of meaningful inclusion in our daily lives, could be examined and expanded so that no child is left out of any teacher’s vision of learning and no person is refused access to our gifts and love.

References

Singleton, G (2006).Courageous conversations about race: A field guide for achieving equity in schools. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.